Contract

Can I sue someone who promised to marry me (but doesn't) in Malaysia?

about 8 years ago JS LimYou’re engaged to the love of your life. The wedding ceremony is set, invitations have been sent, and you’ve even paid the down payment for your new home. But one day, your spouse-to-be breaks it off with no apparent reason.

You’re heartbroken and confused. And after reality sinks in, you need a solution for the hefty sum you’ve already spent on the marriage that isn’t going to happen. Can you sue your ex-fiance for the money?

The answer depends whether you formed a contract when you promised to marry each other. And one essential ingredient of contracts is your intention to be bound by law. Of course, most people don't follow up the "I do" with a "Yay, now please sign this contract!". So, in absence of a written contract that's been signed by you and your (now) ex-fiancee, how does the law decide if you both had such an intention?

The answer: Presumptions.

This will take some time to explain, so if you're looking for a quick answer to the marriage question, scroll right down to the second-last paragraph. Otherwise, let's talk presumptions!

Yep, the law can be a bit of an ass. Credit: eagleonline.com

Is it a commercial agreement, or social agreement?

In many parts of Malaysian law, we follow some English court decisions from a long time ago, which is where we referenced our first laws from. It's from these old English court decisions that we draw two general presumptions for the intention to create legal relations.

In Malaysian law, we recognize that usually formal documents show an obvious intention, and it’s difficult to enforce promises made in casual conversation due to a lack of documented proof. However, we’ll later see that there are exceptions to these rules. There are always exceptions

But let's start off with how presumptions work in these two general rules....

Presumption 1: Commercial transactions $$

Whenever you perform a transaction, the law presumes you intend to form a contract. After all, buying and selling is really just promising money in exchange for goods and/or services! It’s obvious but worth mentioning: when merchants make business transactions in huge amounts of money and goods, the law must enforce these agreements or we’d be in a whole lot of trouble when Ah Beng one day decides to run off with our goods instead of delivering it.

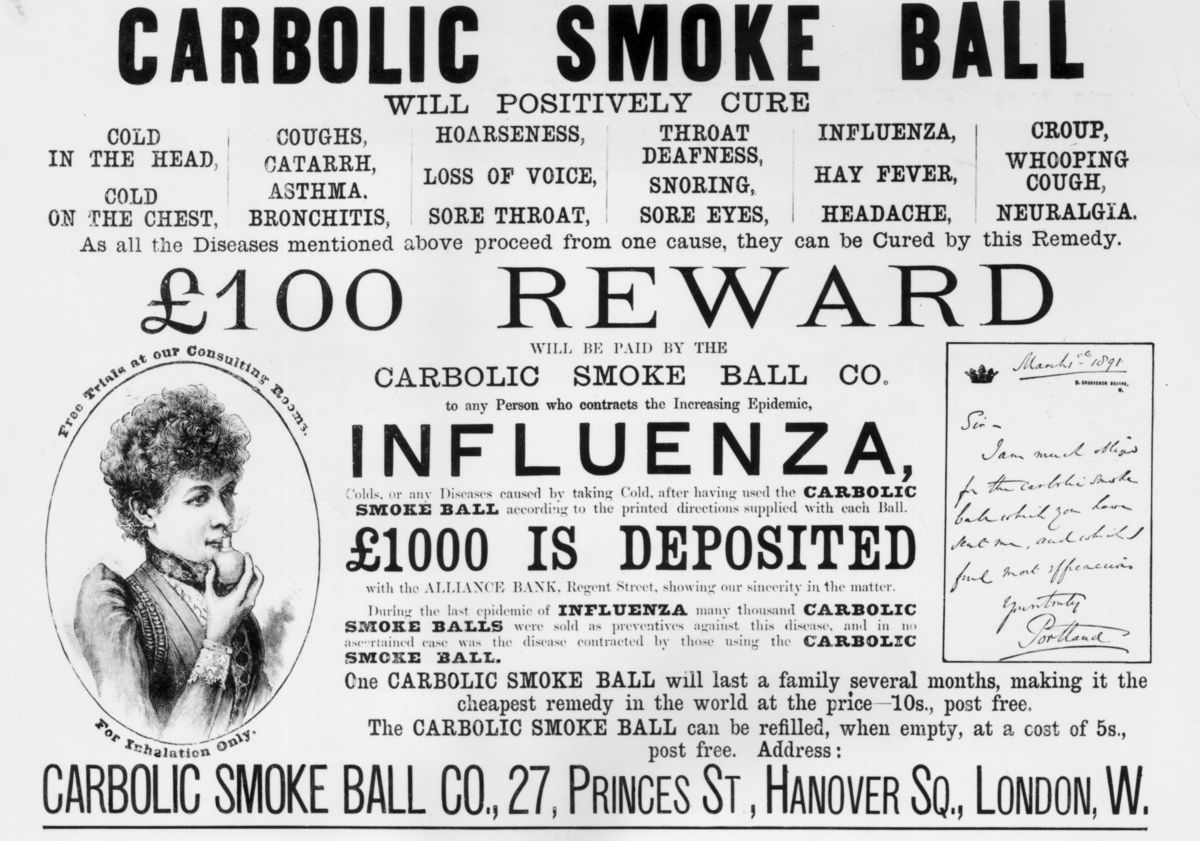

In an old case law, Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co, the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company made a “smoke ball” that they claimed would cure the flu. They had so much confidence in their product that they promised £100 (a lot of money at the time) to whomever caught the flu after using the smoke ball. Ms. Carlill had been using the smoke ball for a few months, but still contracted the flu. No prizes guessing that the company refused to pay her any money.

The test used in court was "how would an ordinary person understand this". Have a look at Carbolic Smoke Ball Co's advert yourself!

The actual ad from 1892. Credit: Huffington Post UK

Read plainly, these are promises made to people to convince them that the company is trustworthy and has a good product. Needless to say, the Court of Appeal decided the £1000 the company set aside for the rewards showed enough sincerity to be bound by law.

Presumption 2: Social agreements

With family and friends, the law assumes that we don’t intend to involve legal consequences. In yet another old case of Balfour v Balfour, a husband promised to give his wife a monthly allowance while his government post abroad kept them apart. Later, after they separated permanently, the husband stopped paying and the wife sued for the allowance.

The Court ruled that in favor of the husband because there are promises in social contexts (even those involving money) which do not form contracts, for example: agreeing to take a walk together. The most important factor is again, whether both parties intended to be bound by law.

We’ve stuck with this presumption for a century because well, it would be weird if the law controlled parts of our private lives. Imagine a lawyer pressuring mum to buy Little Marcus that toy she promised, or suddenly being called to court for the dishes you didn’t wash...

Yeah.

If the marriage proposal was a joke, then you probably won't have a case

Whether in commercial or social settings, the actual intention of both parties still matters more. The setting is a convenient pre-filter to quickly resolve the clear-cut cases, and the finer context is looked at for the unusual ones. Here are some exceptions that the court will consider.

Exception 1: Clearly avoiding a contract

Some of us have run into situations where we’re a “special case” that doesn’t fall within the system. And while the presumption of binding law is helpful in most commercial situations, businesses also require the freedom to create non-binding promises, like Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs). In business, sometimes you don’t know if that deal with your client will be signed (yet), or you might not want to tie yourself down to one supplier for 5 years. In Ayer Hitam Tin Dredging Malaysia Bhd v YC Chin Enterprises Sdn Bhd, it was explained that:

"…when an arrangement is made ‘subject to contract’... it will generally be construed to mean that the parties are still in a state of negotiation and do not intend to be bound unless and until both parties sign a formal contract."

Exception 2: Soured relationships

After a relationship goes wrong, we’re not sure if we can still trust the other person to honour promises. The law is very understanding of this, and will enforce agreements made when parties are not on good terms with each other. In the case of Merritt v Merritt, a couple going through a divorce agreed that the wife would take their matrimonial home if she paid off the rest of their mortgage. She made the payment, but the husband refused to give her the house.

It was decided that because they were a divorcing couple, they would want everything cut and dried, and wouldn’t rely on honourable understandings. So the court decided that a binding contract was indeed created.

Exception 3: Believing in empty promises

Say you’ve agreed to sell your house to your friend because he said you could rent a room at his place, and after your house is sold, your friend tells you that he can’t rent you a room anymore. This kind of arrangement could be merely a friendly agreement, but is also commonly carried out as business contracts.

You’ve made a decision that relies heavily on your friend keeping his promise, to your loss. The law can step in here to protect you. However, if you went to buy a particular company’s shares because your uncle told you “the price can fly soon” though, you’re on your own; the law doesn’t protect reliance on baseless talk.

Exception 4: But I didn't mean it!

Sometimes we say things we don’t mean, like your friend swearing he'll give his car away if Annie would arrive on time for once. The amusing case of Weeks v Tybald had a father advertising a promise of £100 (this was in the year 1605, so it’s big money) to the person who would woo his daughter and marry her - with his consent, of course. The eventual suitor later sued for the promised amount, but the court ruled against him with the reasoning that the promise was not directed to anyone in particular and was therefore not legally binding. Here's the ruling in 17th Century English:

"It is not aver'd nor declar'd to whom the words were spoken, and it is not reason that the defendant should be bound by such general words spoken to excite suitors."

Even when a promise so precise was made it was not considered a contract because this was the kind of statement that we don't seriously mean - it’s just a figure of speech or a joke.

So... can you sue someone who promised to marry you?

Now that you know some of the conditions under which the law will protect your promises, the quick answer is - Yes, you can.

It's all dependent on the facts surrounding the case; and factors like perspective, intention, and the order of events can all affect the outcome. Yet, cases have happened in Malaysia, such as Doris Rodrigues v Bala Krishnan; where Doris sued Bala for breach of promise to marry after Bala married someone else despite the fact that Doris lived with him as husband and wife for several years.

Compensation for hurt feelings, ruined reputation, and marriage costs have also been given in the past. The court can also award compensation to punish the promise-breaker almost entirely at their discretion (see Dennis v Sennyah and Tan Siew Hoon v Lee Lap Shun).

But still, seek advice from a trained lawyer who can help you reach a settlement.

In the end, it's not just about marriage...

The takeaway? Keep trusting your friends and family, but look out for yourself first before you try providing for others, and only give away what you can afford to never see again.

To conclude with a common example: your friend wants to borrow a lot of money from you. Whether or not you trust her, it would be best to put it in writing if it’s important enough to iron out the details. Also, even when the law is on your side, the practical measure is to settle the matter outside of court, and to be prepared with alternative solutions like holding your friend’s car as security in your agreement. Legal fees are expensive, and court proceedings can take months to settle. Tread wisely!

Remember: the protection from contracts is not for when everything is fine, they’re for if things go downhill!

P.S: If you're interested to find out what happened in the case laws, they usually require a subscription for online access. We managed to find a few sources for you as linked above, as well as this article which explains a few cases on the intention to contract.

Jie Sheng knows a little bit about a lot, and a lot about a little bit. He swings between making bad puns and looking overly serious at screens. People call him "ginseng" because he's healthy and bitter, not because they can't say his name properly.